To start the 2025 new year, Cornelia whisked Cambodian chorabab brocade artisans off to Surin, Thailand. The purpose of the trip was to network Cambodian and Thai weavers, find out more about the roots of Cambodian patterns, get a copy of training materials for setting up a pattern in a loom (there are less than 20 pattern setters left in Cambodia, and no written instructions), and locate sources of indigo dye, less-expensive silk thread, and black thread (most Cambodian chorabab is made with black warp, but only white thread is available in Cambodia).

The trip was made possible by a research grant from the Victoria and Albert Museum (London), Karun Thakar Fund. All of the artisans were thrilled to have such an opportunity! Most had never been outside of Cambodia before.

We started at Ban Tha Sawang silk weaving village, just 10 kilometers northwest of Surin City. Master Viradham Trakoonngeunthai and Nirundra Sailegtim spent half a day answering our questions about the origins of brocade patterns in Southeast Asia – in English for Cornelia, and in Khmer for our Cambodian chorabab artisans. Master Viradham and Nirundra also speak Thai.

From left, pattern setter Srey Neith Lok, Master Viradham Trakoonngeunthai, Nirundra Sailegtim, researcher Cornelia Bagg Srey and chorabab designer/producer/weaver Makara Lok. Srey Neith is one of less than 20 pattern setters left in Cambodia. Makara has 48 weavers on her staff.

We showed them several Cambodian patterns - quite different than Thai patterns.

The next day we networked with the weavers at Ban Tha Sawang, learned about Thai patterns and how they’re woven on pit looms, and observed the process of making indigo dye. We looked at the different products they make, and how they’re sold at retail (branded, labeled, tagged and displayed). Nirundra gave us advice on how to sell online to customers overseas.

The main brocade weaving hall at Ban Tha Sawang, constructed from recycled wood. The floor is elevated to accommodate the pit looms. The weavers have cool, fresh air because of the trees, and natural sunlight. No need to cut anything down – just leave space in the roof!

Three of Ban Tha Sawang’s master brocade weavers. From left, Tin Kaewta, Samriap Hantula and Sombat Ngamden.

Left, Nirundra Sailegtim showing us traditional Thai patterns. Right, Makara Lok (with master dyer Somrung Sorakanit) savoring the smell of thread just out of the indigo dye bath.

The Chan Soma retail store at Ban Tha Sawang. Upscale, welcoming, cozy and cool, with everything clearly labeled - brand and logo, price, care instructions, and contact information.

The following day we went to the Queen Sirikit Sericulture Center.

Left, Makara and Queen Sirikit Center staff exchanging tips for raising silkworms. Right, learning how antique brocade is stored at their museum.

We went to Khwao Sinarin silk weaving village hoping to meet with weavers there, but were told upon arriving that weaving has died out in this village.

Back in Surin City, we were able to locate sources of black thread:

—> Nong Ying Silk Shop, 52 – 58 Jitbumrung Road (near the bus depot and the railway station). Facebook: @silksny. Telephone: +66 281-7614. E-mail: silkny@hotmail.com.

—> And around the corner, AekAnant Thaisilk, 122 - 124 Sanitnikomrat Road. Facebook: @aekanantthaisilk. Telephone: +66 044-511441, 081-6002-329, 093-456-6693, 081-547-4237.

Nong Ying Silk Shop, selling weaving supplies on the right and finished products on the left.

Left, Benjaporn Sombatmaithai showing Makara the quality of their black thread. And look behind them, at all the other colors available! In Cambodia brocade producers can buy only white. Right, we found loom parts that were slightly different than their Cambodian counterparts. Makara bought some to try them out.

The purpose of the trip was to network Cambodian and Thai weavers, get a copy of training materials for setting up a pattern in a loom, find out more about the roots of Cambodian patterns, and locate sources of indigo dye, less-expensive silk thread, and black thread.

The Ban Tha Sawang center did not develop written training materials for setting up a pattern in a loom, but this is as we expected.

We were not able to locate a source of indigo dye for purchase because not enough is produced, but the Ban Tha Sawang center offered to teach us how to make it (they said that Cambodian indigo makes just as good dye as Thai indigo).

We found that the silk thread available in Surin was not less expensive than that available in Cambodia.

But we found two sources of black thread, and colored thread; this will increase chorabab producers’ profit margins, and decrease human error in the dying process and environmental pollution in their villages.

We found loom parts that were slightly different than their Cambodian counterparts, and bought some to try them out.

We saw how silk is sold at retail in Thailand, and got advice on how to sell online to customers overseas.

We saw two different methods used by museums to store antique textiles – one at Ban Tha Sawang, the other at the Queen Sirikit Center.

Cornelia has interviewed experts from around the world on the roots of Cambodian patterns, and found Master Viradham Trakoonngeunthai and Nirundra Sailegtimto to be very knowledgeable. And generous with their time.

At Ban Tha Sawang we saw the efforts made to minimize damage to the environment. The use of recycled wood and minimal use of cement, the preservation of old trees and the planting of new ones.

And networking was easy. We found the Thais we consulted to be friendly, knowledgeable, caring and helpful.

All considered, our research trip was far more productive than we could ever have anticipated.

*************************

We made a second trip in February, and this time, Makara Lok’s father was able to come with us. He is known as “Om Jap”, and was Kikuo Morimoto’s right-hand man at I.K.T.T. in Siem Reap for 15 years. His family has been making chorabab brocade for six generations. He just turned 85, and had more energy that all of the rest of us!

We returned to AekAnant Thaisilk to learn more about their thread, and Makara bought more loom parts.

We returned to Ban Tha Sawang for a second interview with Master Viradham Trakoonngeunthai and Nirundra Sailegtimto on the roots of Cambodian patterns.

We visited the weaving workshop in Wat Phi A-jhiang temple in the northeastern part of the province.

We toured Maiithong Surin in the weaving village of Ban Mai Thong Saren; they specialize in silk ikat. Our host was Mrs. Krittika Pakdeerath. If you would like to visit them take their telephone number with you, as your driver may need to call them for directions. Telephone +66 087-246-3434. E-mail krittika_pak@hoitmail.com.

Our last stop was Ban Sawai, a weaving village near Ban Mai Thong Saren. The Boonsodakong family uses a special type of lac to get various shades of pink. Their brand is Royal Thai Silk. Of all of the ikat we saw in Surin we liked theirs the best, because of the softness of the color.

If you’d like to visit any of these weaving villages, we’d like to recommend our tuk-tuk driver to you. Mrs. Angchali Khemkor, telephone +66 089-714-5408. The best!

Our host at Wat Pha A-Jhiang temple, Nachol Rich, showing Cornelia silk dyed with elephant dung. Right, Makara studying the pattern arrangements unique to this area.

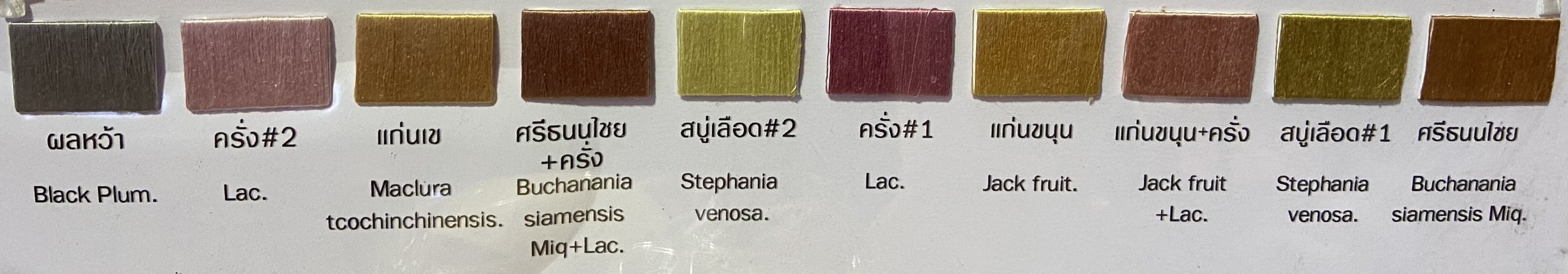

At Maiithong Surin in the weaving village of Ban Mai Thong Saren, a guide to their natural dyes.

At Ban Sawai, a special type of lac is used to get a soft rose color. Right, out host Samneang Boonsodakong and her daughter-in-law show us a piece made 100 years ago. “Om Jap”, Kikuo Morimoto’s right-hand man for 15 years, is on the left. Below, the Boonsodakong family’s showroom in their home.

For all of us, it was an incredible journey. The best part? The people we met. Like Ailada Mala at Ban Tha Sawang, who knows how to keep warm on a chilly Surin morning.